Esther & Rachel Carillon

Twelve-year-old Esther Carillon (sometimes spelled Carillion) and her younger sister Rachel, were the first children taken into the Home’s care in June 1855, eight months before the orphanage was built. The board paid Anna DePass, the widow hired to serve as the Home’s matron, to temporarily shelter the girls in Mandeville, Louisiana, a summer retreat from the city’s heat and yellow fever fever on Lake Pontchartrain’s North Shore. After being assured that DePass was paying “every attention” to the girls’ well-being, the board appropriated ten dollars (approx. $360 today) for shoes and clothing “of which they stand sadly in need.”

Registry pages for Esther and Rachel Carillion [sic], the first two children taken into the Home’s care. Courtesy JCRS.

Esther and Rachel were daughters of Reverend Benjamin Cohen Carillon, a native of Amsterdam who earlier served a congregation in Jamaica, and the former Rebecca Levy, who worked as a dressmaker upon the family’s arrival in New Orleans in 1848. Although the precise circumstances of his and his wife’s deaths are undocumented, Rabbi Carillon’s difficult tenure in Jamaica (where his traditional Sephardic congregation opposed his reformist innovations) left him unable to secure a pulpit in New Orleans. Although he reportedly delivered a sermon on Sukkot in 1848 at Gates of Mercy Synagogue, the 1850 census described the Jewish clergyman as “insane.”

When Esther and Rachel entered the Home, they had four surviving siblings: Aaron Charles and Miriam were older, while Judith and Rose Sarah were younger. Of the Carillon children, only Esther and Rachel were admitted to the Home.

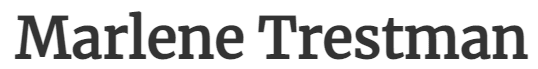

Text of certificate issued by Rev. Benjamin Cohen Carillon in April 1844 in St. Thomas of today’s Virgin Islands to mark Hannah De Sola’s confirmation, which reportedly predates by two years the earliest recorded confirmation ceremony by any synagogue on the North American continent.

In 1859, at age 16, having completed her studies at the public school, Esther performed housework in the Home for which she earned six dollars per month. She also captured the heart of Herman Gilbert. Seeking the board’s permission to marry its charge, the thirty-one-year-old house painter wrote that he was capable of supporting Esther and pledged to make her happy.. Recognizing the decision’s importance as precedent for other female inmates, the board acceded to Gilbert’s request. In addition, the board appropriated one hundred dollars to provide Esther a wedding trousseau. The practice of providing funds when Home girls married was later institutionalized in 1900, courtesy of a fund endowed by Simon Gumbel, a prosperous merchant who served as the Home’s treasurer for fourteen years. The gift to Esther was the board’s first generous act of its kind, consistent with marriage then being the most desirable outcome in life for a young woman.

In October 1860, the board dispensed with its regular meeting to celebrate Esther’s nuptials in the Home. Reverend James K. Gutheim officiated in the presence of the board, the honorary matrons, and what the minutes described as “a large concourse of friends” of the couple. Although Esther left no account of her views about marrying Gilbert, they remained married for four decades until his death, when he was eulogized as “industrious, honest, and generous.” She bore him thirteen children.

Esther died at age 91 on January 7, 1933, the same day that the Home celebrated its 79th anniversary. She was buried in New Orleans’s Dispersed of Judah Cemetery, alongside her husband.

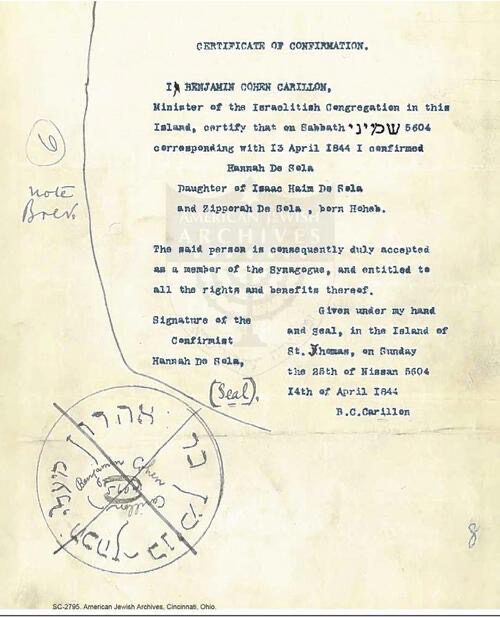

Headstone of Esther K. Carillon Guggenheim and her husband, Herman M. Gilbert Guggenheim. From Find a Grave.

Esther Carillon Gilbert Guggenheim, undated. Courtesy of her great-great-gradndaughter, Rose Gilbert.

Herman Morris Gilbert Guggenheim, undated. Courtesy of his great-great-granddaughter, Rose Gilbert.

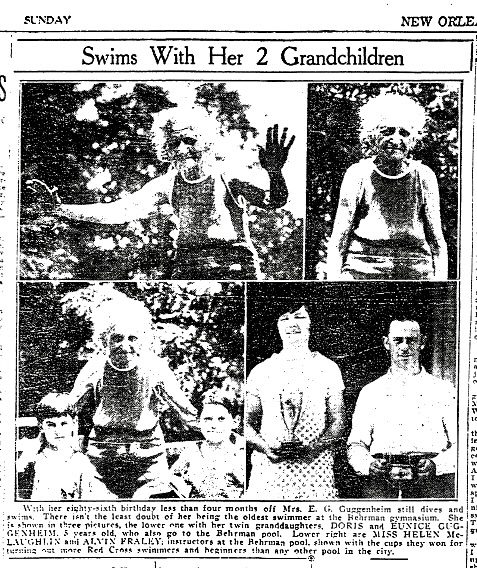

In 1928, a few months before her 86th birthday, Esther was featured in these photos and a news article, “Woman 86 Swims, Dives and Dances,” New Orleans States.

Rachel also left the Home in 1860, discharged into the care of her other married sister, Miriam, and Miriam’s husband, Jacques Oliveira, a Dutch violinist who in 1863 and 1866 performed benefit concerts for the Home. (For more about Jacques Oliveira, see Brian Thompson, “Journeys of an Immigrant Violinist: Jacques Oliveira in Civil War-Era New York and New Orleans,” Journal of the Society for American Music, 2012 (51-82). In 1886, Rachel married Adolph Theodore Von Konigslow, a widower with six children, who was listed in the 1906 city directory as a pattern maker.

Rachel died in 1939 at age 93, just one year after having been celebrated as the city’s “oldest living mother.” She was buried in New Orleans’s Greenwood Cemetery next to her husband.

‘Oldest’ N.O. Mother Dies – Rites Monday for Mrs. Von Konigslow

Mrs. Rachel Carillion Von Konigslow, 93, who was selected last Mother’s Day as the oldest living mother in the city, died at 12:55 o’clock Saturday afternoon at her home, 2319 Baronne St.