Rose, Maxine, and Joe Bihari

In 1930, Hungarian immigrants Edward Bihari and his wife, the former Ester Taub, were living in Tulsa, Oklahoma with their eight children, when Edward died. The next year, Ester admitted her three youngest children – Rose (10), Maxine (8), and Joe (6) — to the Home.

Rose lived in the Home until 1938, following her graduations from Tour Synagogue Religious School and from Joseph P. Kohn Commercial High School for Girls. She returned to her mother and older siblings in Tulsa, Oklahoma. Later known as Roz or Rosalind, she later relocated with her family to Beverly Hills, California, where she worked as a business secretary with Roz and older sister Florette in her older brothers’ phonograph record factory.

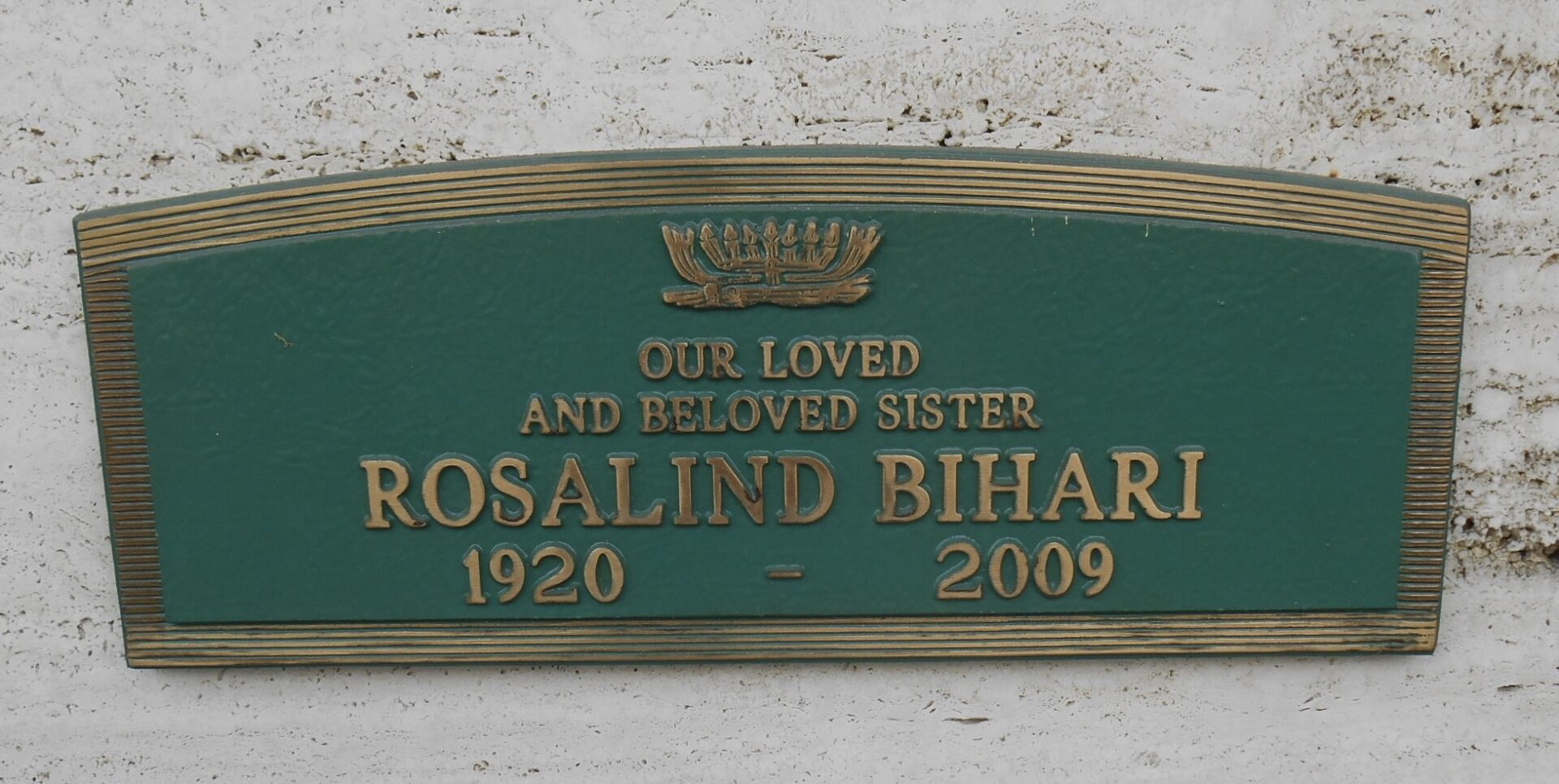

Roz, who remained unmarried, died in 2009 at the age of 88 and was buried in Hillside Memorial Park in Los Angeles.

Burial marker of Rosalind (Rose) Bihari. From Find a Grave.

During her time in the Home, Maxine played a role in the institution’s 1933 musical-pantomime production of “Alice in Wonderland” before celebrating her 1937 graduation from Touro Synagogue’s religious school. After earning her diploma from Joseph P. Kohn Commercial High School for Girls in 1942, Maxine also returned to her mother in Tulsa.

In 1950, Maxine married Irving J. Kessler, with whom she had a son and daughter. After her marriage ended in divorce, Maxine remained in Los Angeles where she joined her sisters in working in the family’s record business.

This photo of 16-year-old Maxine Bihari (center) shopping for a dress with Girls’ Supervisor “Aunt” Sonya Berger (right, in hat) appeared in the Home’s 1940 brochure, “Tell-A-Vision.” Courtesy of JCRS.

Maxine died at age 76 in 2000. According to her April 20, 2000 obituary in the Los Angeles Times, “Max is also survived by hundreds of people whose lives were touched profoundly by her dedication, courage, and love…Her life was devoted to bringing overwhelming joy and life to all people within her presence.”

Maxine Bihari, at right, gives a manicure to a fellow Home resident (unidentified). From “Tell-A-Vision” brochure, 1940. Courtesy of JCRS.goes here.

Joe Bihari lived in the Home until 1943, when he returned to his mother who had relocated to Beverly Hills. Having left Isidore Newman School before graduating, Joe completed his secondary education in a local public high school.

It was during his time in the Home that Joe developed his love for music, a passion that would impel his future career in the music industry. As Joe said during a 1995 interview, “My interest in blues started when I was fourteen years old at the Home from one of the maintenance men, Matthew Causey, who lived right on the property….I used to go to his apartment and listen to some of the old blues singers: Memphis Minnie, Blind Lemon Jefferson, Doctor Clayton, Robert Johnson….I’d go down and listen for hours and hours.”

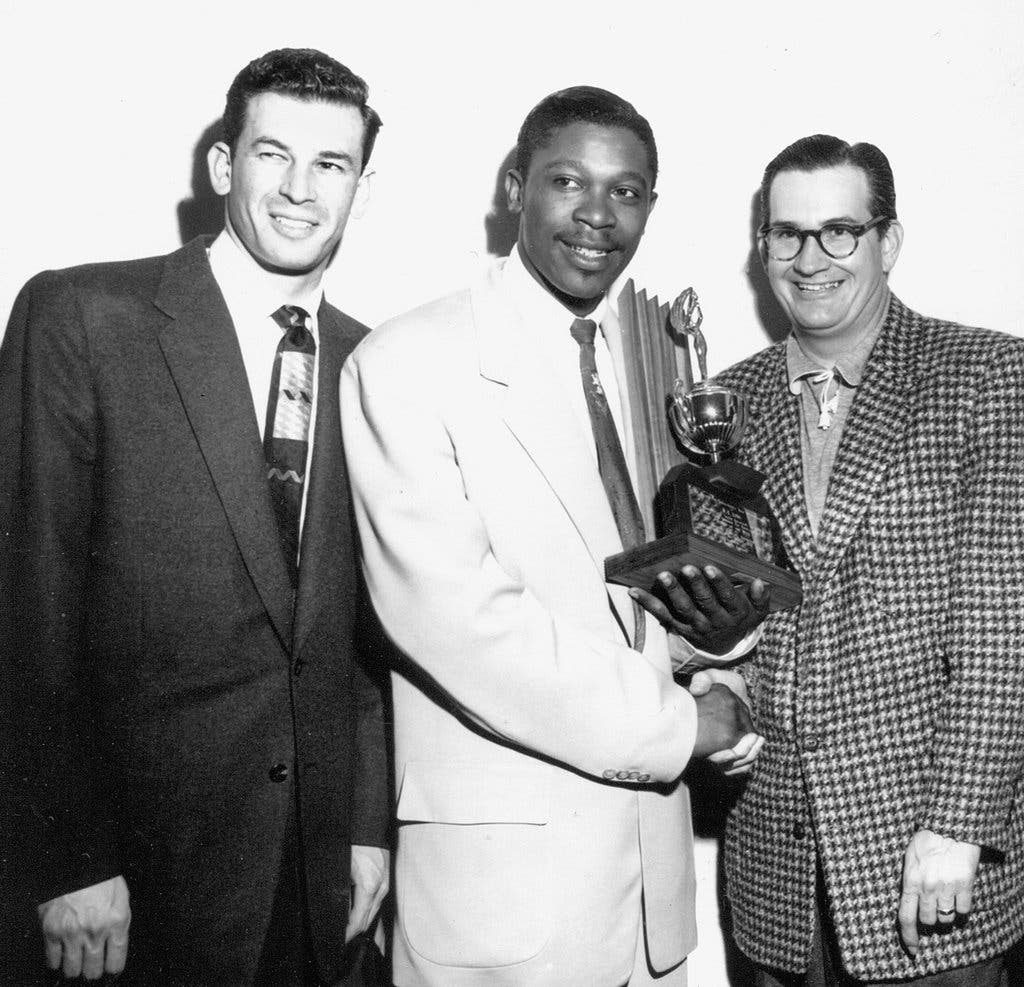

By this time, Joe’s older brothers (Jules and Saul) had started a jukebox business that created a distribution network across several states. In 1945, to address the shortage of records for their machines, the brothers created Modern Music Records (later Modern Records) that recorded, pressed, and distributed blues and rhythm and blues records for the next three decades. Most of the Bihari siblings worked for Modern at one time or another All of the brothers scouted and signed new artists, but Joe specialized in this aspect of the business, often traveling with a young Ike Turner to find and record talent in remote locations. In addition to releasing some of the first widely distributed recordings of blues legends including John Lee Hooker and Etta James, Joe and Modern helped make B.B. King and Ike Turner stars.

Although the Los Angeles press reported in the early 1950s that he was romantically linked to the daughter of California Governor (and future Supreme Court Chief Justice) Earl Warren, Joe married Doreen Kline in 1975. Together they raised a son and two daughters.

In 2006, for their pioneering contribution, impact, and overall influence on the Blues, Joe and his late brothers were inducted into the Blues Hall of Fame. But the Biharis’ relationships with Black artists was not without criticism. “In later years,” reported the Times-Picayune, “B.B. King and other performers told press the white record men had practiced the then-common tactic of giving themselves songwriting credit on recordings, to share in royalties.” The Biharis denied exploiting their artists, saying the songwriters were paid well for their songs.

Joe Bihari died in 2013 at age 88 in Los Angeles. Considered a pioneer in the music industry, his death and his accomplishments were widely reported, including by the New York Times (“Joe Bihari, Who Put Early R&B on Record, Died at 88”), Los Angeles Times, Washington Post, and New Orleans’s Times-Picayune. As music historian John Broven, who interviewed Joe extensively for his 2009 book (Record Makers and Breakers: Voices of Independent Rock ‘n’ Roll Pioneers), Modern Records “was part of this great independent label explosion in the 1940s and 1950s that really put rhythm and blues and blues music on the map” when it previously had been limited to Black audiences. See also, “RIP: Joe Bihari,” The Louie Report, Dec. 13, 2013.

Joe Bihari, left, with Blues legend B.B. King and Disk Jockey Hunter Hancock in 1954. From New York Times.

In His Own Words

In 2009, on the launch of John Broven’s book (“Record Makers & Breakers”), Joe Bihari was interviewed on “Fool’s Paradise with Rex” on Radio Station WFMU. Click here to listen to Joe briefly describe his career in the music industry (starting at about 59:00).