Max, Fannye, and Ruby Block

In 1904, while living in Nashville, Tennessee, divorced Russian immigrant Cecile Lusky Block admitted her 7-year-old son Max and 5-year-old daughter Fannye to the Home. Five years later, Cecile admitted her youngest child Ruby, who was almost eight.

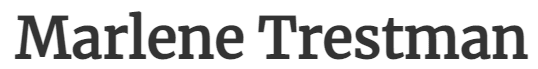

Although Ruby lived in the Home for only one year before returning to Cecile, who had moved to New Orleans where she worked as a tailor, Max and Fannye remained for a decade. While in the Home, Max (whose nickname was “Bud”) served as a Big Brother in the Home’s Golden City self-government and, as Clinic Officer, ensured that his peers visited the infirmary to attend to their bruises and ailments. In 1915, Fannye made news for her role in “Mrs. Plodding’s Nieces,” a one-act comedy nine girls performed on the occasion of the Home’s 60th anniversary.

Siblings Max and Fannye Block, undated. All photos courtesy of Julie Likes, granddaughter of Fannye (Faye) Block Strauss.

Although the play lauded female domesticity, Faye (as she was later known) did not limit herself to her roles as wife (three times), mother of a daughter, or homemaker. She worked throughout most of her life, from her early jobs as a stenographer in New Orleans, a secretary in New York, and later a steno clerk for several federal government agencies in San Francisco. As a reference for her job with the U.S. Department of Commerce, Faye listed Judge Louis Yarrut, a member of the Home’s board and an alumnus with whom she had grown up. Faye died in 1976 at age 77.

Undated photo of Fannye Block in the Home’s courtyard.

Three years after his discharge from the Home, Max entered the military to serve on the Mexican border. When war with Germany broke out, Max trained at Camp Beauregard in Pineville, Louisiana before being assigned to the 149th Field Artillery of the Rainbow Division. When the armistice came, his family falsely believed his life had been spared. A few days before receiving news of his death, a letter arrived in which Max wrote, “We are in mud and water up to our necks. It has missed raining only two days, but even on those the sun did not come out. But that’s all right, Sis, I know there is still some sunshine left in the world and it’s in the dear old U.S.A.” Upon learning of Max’s ultimate sacrifice, Home Superintendent Leon Volmer praised the former ward as one of the “model inmates of the institution, with truth, honesty and loyalty as his ideals.” “Orleanian Killed in Last Fighting; Maxwell Block Receives Death Wound Defending Flag in Argonne,” Times-Picayune, June 29, 1919.

This photo of Max “Bud” Block with four unidentified boys was taken only four years before he died fighting in France’s Argonne Forest in the First World War. He was buried in the Meuse-Argonne American Cemetery in Romagne, France.