Aubrey & Norman Mayer

In 1923, nearly five years after the death of husband, Jesse Louis Mayer, Margot Mannison Mayer admitted her two boys to the Home from El Paso, Texas. Aubrey Edward was 8 years old and Norman David was 7. After the boys entered the Home, Margot relocated to New Orleans where she worked as a nurse.

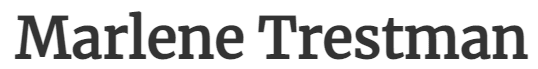

Aubrey, known as Edward in his youth, lived in the Home for nine years, before returning to his mother. After his freshman year, he left Isidore Newman School to attend Samuel J. Peters Commercial High School for Boys, where he completed a three-year bookkeeping course. He returned to Newman for his senior year and graduated with the Class of 1933.

He later married Beth (“Betty”) Spiegal with whom he raised two children in California. After joining the Army in 1942, Aubrey served in the southwest Pacific as a clerk in a tank destroyer unit and later became an administrative warrant officer. He spent his career as an Army officer.

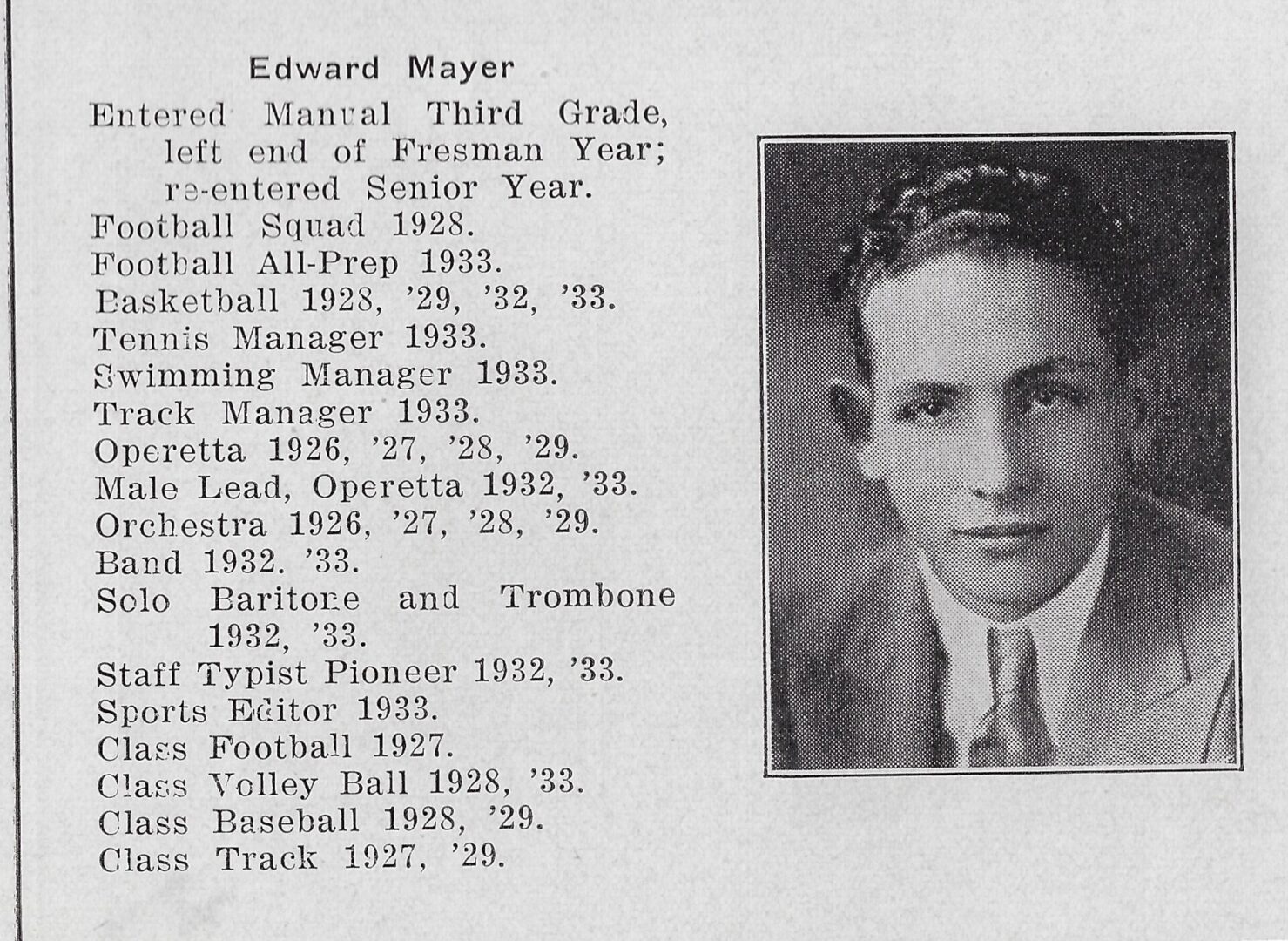

Aubrey died in 1996 and was buried in Fort Rosencrans National Cemetery in San Diego.

The Isidore Newman High School senior yearbook entry for Aubrey Edward Mayer, known as Edward in high school, reflects his wide range of interests and activities. Thanks to Genie McCloskey, Isidore Newman School archivist, for supplying the photo.

From Find a Grave.

Aubrey’s younger brother, Norman, lived a far more fraught life. As Aubrey later recounted, by the time Norman — nicknamed “Buddy” — was a teenager in the Home, he had become the belligerent rebel he remained all his life. “Buddy was always in trouble,” said Aubrey. “He had broken fingers and casts on his hands from fighting in school. He didn’t participate in organized anything….He read Marx, Dos Passos, and Upton Sinclair and was influenced by some older young people who were lefties.”

Aubrey also said that after Norman was “kicked out” of Newman School, he went to Delgado Trade School where he learned tool-and-die making, a craft he later practiced around the world.

After leaving the Home in 1933, Norman traveled to Alaska, Nevada, California, Florida, Virgin Islands, and Puerto Rico working as an oil-rig roughneck, gold miner, helicopter machinist, and maintenance engineer. He became disillusioned by the Vietnam War and, having sustained a broken leg while working on an oil rig off Brunei, traveled across Southeast Asia, India, and Kenya. In 1976, he was arrested in Hong Kong with nearly 45 pounds of marijuana for which he spent 10 months in jail. Although initially sentenced to three years in prison, Norman’s threatening statements prompted the judge to confine him to a psychiatric facility, where he remained until his successful appeal led to his 1978 deportation.

Once back in the United States, at first in Miami before traveling to Washington, D.C., Norman turned his attention and distrust of the government to nuclear disarmament, which became his obsession. By August 1981, his search for a national audience led him to keep a vigil in front of the White House every day for three months, from morning to sundown. By Thanksgiving, discouraged and disillusioned that his protests were ineffective, Norman devised his final — and fatal — scheme.

At 9:20 a.m. on December 8, 1982, wearing a blue snowsuit, a black motorcycle helmet, and a backpack with a protruding two-foot antenna, Norman emerged from the truck that he had driven to the base of the Washington Monument. A captive nation watched on television as he threatened to ignite 1,000 pounds of explosives and refused to negotiate his single demand: Ban Nuclear Weapons. Tragically, the U.S. Park Police did not know he was bluffing: his attempts to purchase dynamite had been unsuccessful. After ten hours, as Norman got back in his truck and began driving away from the monument with the apparent intent to carry out his threat, the bullets of nine sharpshooters hit Norman twice in the arm, once on the tip of his chin, and once in the left temple. According to the Park Police, Norman Mayer had pulled off the longest terrorist bluff in U.S. history. As Aubrey later commented, “He wanted to go out in a blaze of glory and he did it.”

Sources: Joe Pichirallo and Blaine Harden, “The Odyssey of Norman Mayer: Victim of an Unyielding Will,” The Washington Post, Dec. 19, 1982; Cassandra O’Hara, “One Man’s Radical Plan to Blow Up the Washington Monument”; “Law and Disorder: Examining the Washington Monument Siege,” National Law Enforcement Museum.

Even in death, Norman Mayer caused controversy. Honoring his service as an honorably discharged seaman, Mayer’s cremated remains were placed in a columbarium at Arlington National Cemetery, over the formal protest of Army Secretary John Marsh. “Slain Peace Activist Buried at Arlington,” Washington Post, Dec. 19, 1982.

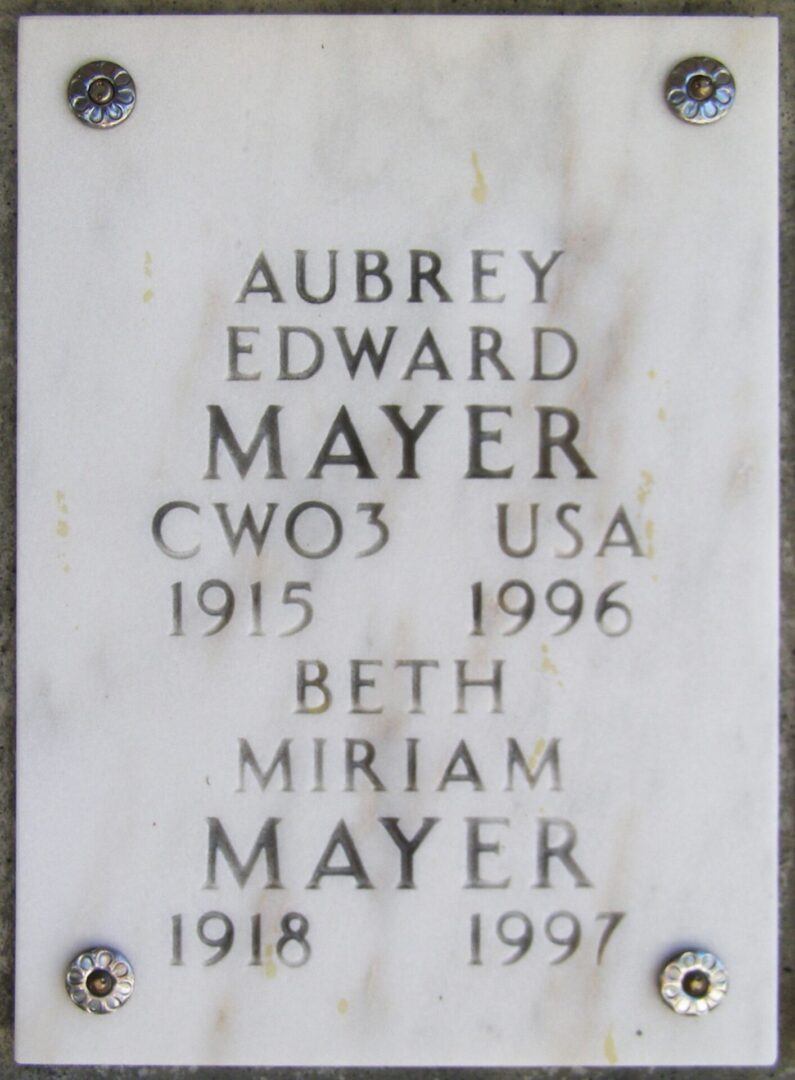

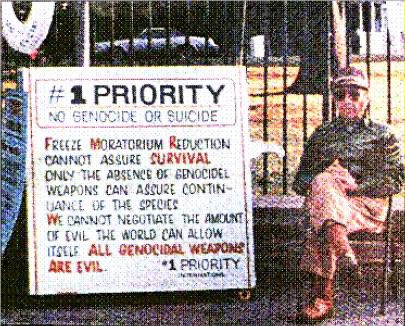

Norman Mayer, during his three month vigil outside the White House in the summer of 1981. From Find a Grave.

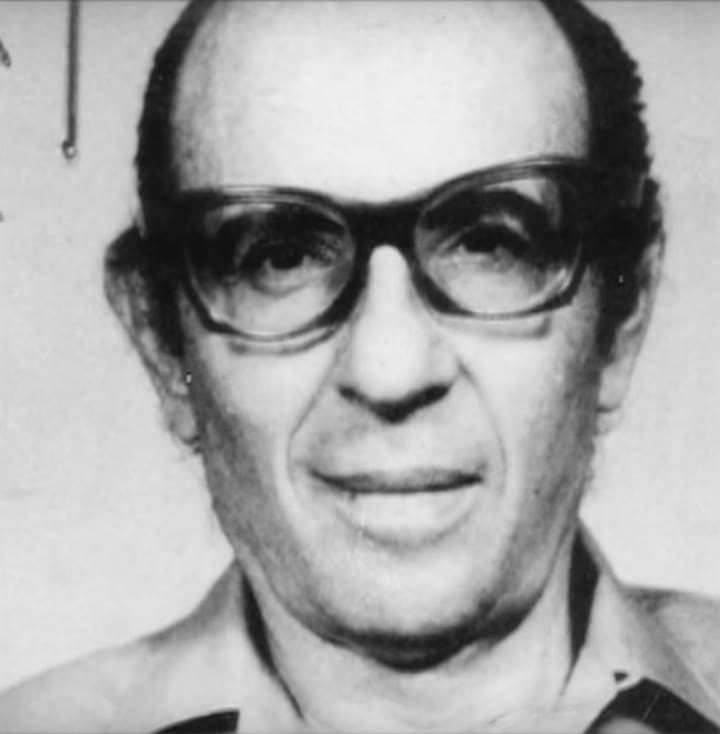

Norman Mayer outside the truck he drove to the base of the Washington Monument, Dec. 8, 1982. From VocalMedia.com.

Norman Mayer’s threat to blow up the Washington Monument captured the nation’s attention, including on the front page of the New York Times. During the siege, nearby government buildings were vacated and President Reagan moved his meeting to a more distant room in the White House. Watch the AP footage, “Ten Hour Siege at Washington Monument.”

Photo from Find a Grave.